Invisible minorities

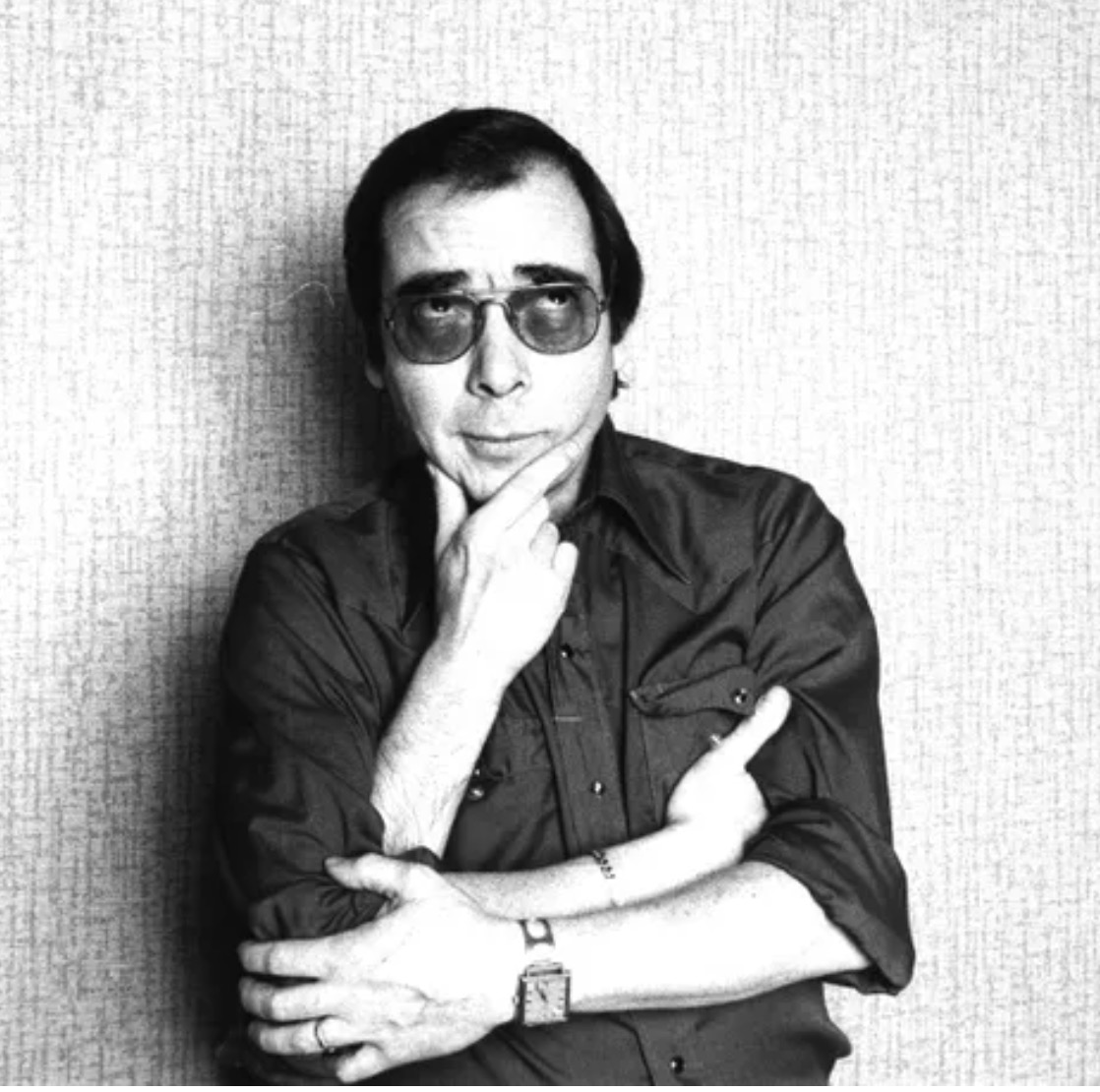

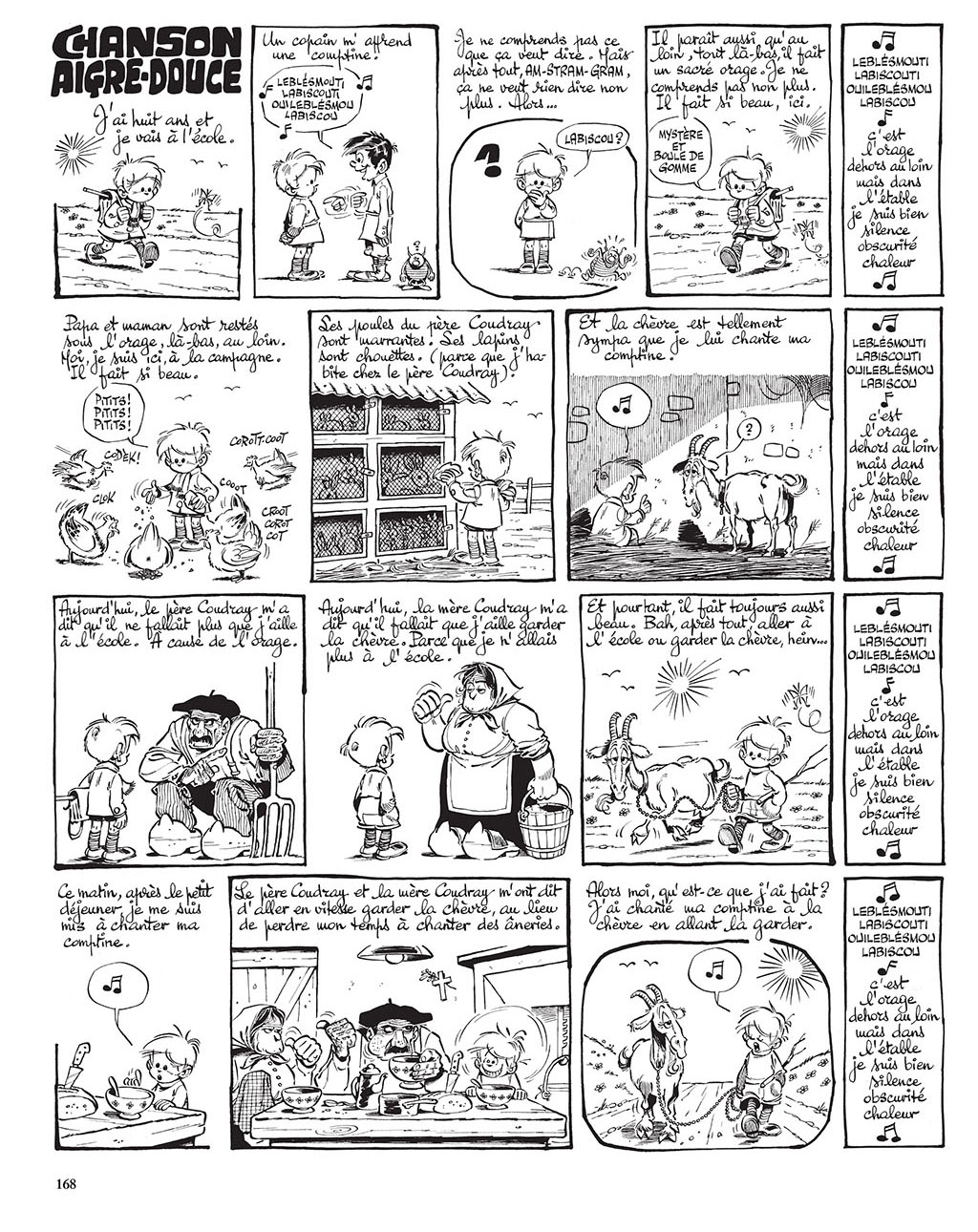

David B: Do you know this character? He is a French comic book author named Marcel Gotlib. He worked for a French magazine, "Pilote", he did humorous comics and I loved him when I was little, we would talk about him amongst friends at school. One day a comic very different from all the others came out in "Pilote", it was called Chanson aigre-douce and it was very serious and a little melancholic. In the story there was a recurring rhyme that did not make much sense to me upon first reading. The comic was about the country life led by the main character, who lived on a farm with some farmers who were not his parents and with his only friend, a goat.

I was ten when I first read it, then I reread it around twelve or thirteen and I finally understood everything: it was not about the protagonist's holidays in the countryside but about a thunderstorm! The main character is forced to go to the countryside because there is a storm! It then took me some more time to realize that the storm was World War II and that his parents had sent him to the farm to hide because he was Jewish. So he had to spend the whole war in a family that was not his own, taking care of this goat and not being able to go to school anymore because it was too dangerous. Suddenly the comic became incredible: it never contained the words "war", "jew" or "Nazism", it did not describe anything.

I later found out that Gotlib had taken this story to René Goscinny, the director of "Pilote", not knowing if he would publish it. Goscinny was Jewish as well, but he had spent the wartime period in Argentina and hadn't experienced the persecutions. After reading those two pages he chose to publish them immediately, no questions asked.

This was the first autobiographical comic I ever read in my life, I was ten years old. But I only thought about it much later, after doing L'Ascension du Haut Mal.

The reason it had touched me was that, during my holidays, I went to a small town called Châteaumeillant in central France, my mother's country of origin. My mother experienced the war there. She came from a peasant family like the one Gotlib tells about. There were no Jews in that village, there were no minorities, the only person who came from outside was called Papazoglou, he was a Greek-Turkish man who fled persecution and became the county doctor, and so he was accepted because of his role.

Gotlib's comic reminded me of some family stories my mother used to tell me. When the war broke out, refugees arrived in the village, including some Jews who came from Paris. These people became very important to my mother.

You have to keep in mind that she lived in a small village of three hundred people, without any cultural life whatsoever, and suddenly she saw these Jews coming from Paris who could read, who dressed well, who bathed in the only place where you could bathe in Châteaumeillant.

My mother always told me that they had well made bathing suits, bought in the shops of Paris, while the peasants of Châteaumeillant wore knitted woolen suits which, when wet, became hideous. The Parisians, on the other hand, were beautiful and made her dream.

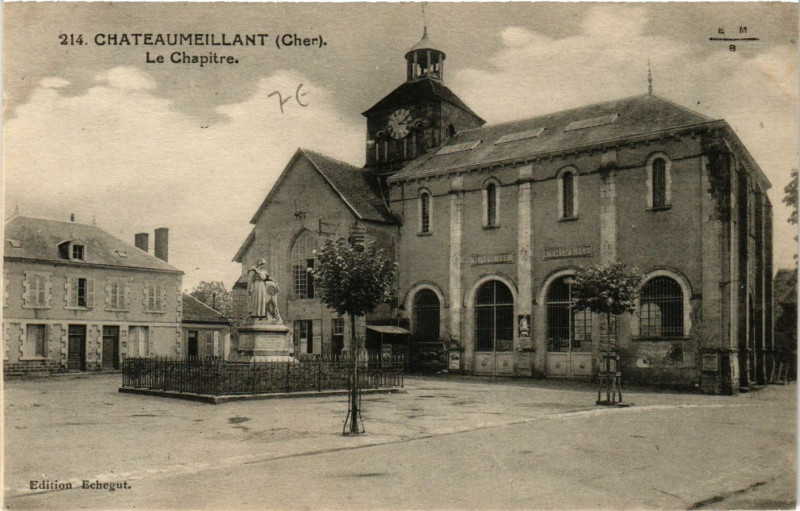

Among these Jewish refugees was a singer from Paris's Opéra-Comique who, to thank the people of Châteaumeillant for their welcome, organized a show in a place called Chapitre, a deconsecrated church that had been transformed into a space for the farmer's performances and meetings.

When my grandfather went to see the show, he had never met a Jew in his life. When he got back home, they asked him what the singer had done, and he replied: "He sang Jewish songs dressed as a Jew."

My grandmother then inquired and discovered that during the show some pieces of Les Contes d'Hoffman had been sung, an operetta by Jacques Offenbach based on Hoffman's stories, who in addition to being a writer and a musician was also a draftsman. They weren't Jewish songs, but a collection of German nineteenth-century characters. This is to explain what my grandfather's amazed gaze was in front of people who were incredible to him.

As a girl my mother studied at the Lyceum of Châteauroux, the largest city that was near Châteaumeillant. Another event that would be very important for her took place ther: in her class there was a man named Saul Friedländer, a Jew refugee. He and my mother were in competition because they were the best in the class, especially in literature. Once my mother got a higher grade in a class test, and Friedländer dedicated a poem to her. It wasn't a love poem, it was a poem to tell her that she was very good, better than him. My mother remembered this poem fifty years later, and she recited it to me; at the time I did not think to write it down and that is really a shame because now my mother died and it is lost.

Over the years, Friedländer became an important writer, a Holocaust historian, he went to live in Israel and was also mayor of Jerusalem. He has written a book of memoirs in which, however, there is no mention of his period in Châteauroux; when she read it, my mom was very sorry that there was no mention of that period, of that cultural struggle. She always talked to me about it, she told me: "I don't understand why he doesn't mention it in his memoir".

I then also read the book and it was true, he had dismissed everything in a sentence: "I went to the Lyceum of Châteauroux", and that was it.

My mother was always interested in culture, literature, ideas, art, and always tried to meet great French intellectuals. She once wrote to Simone de Beauvoir, who at the time was a great intellectual figure in France. There were two intellectuals, Jean Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, and luckily they lived together so my mother only had to write once. But she never got a reply.

She later became fascinated by Raymond Abellio and his novel Heureux les Pacifiques. He was known as an esotericist and was very interested in the Cathar religion, which my mother was also very fascinated by.

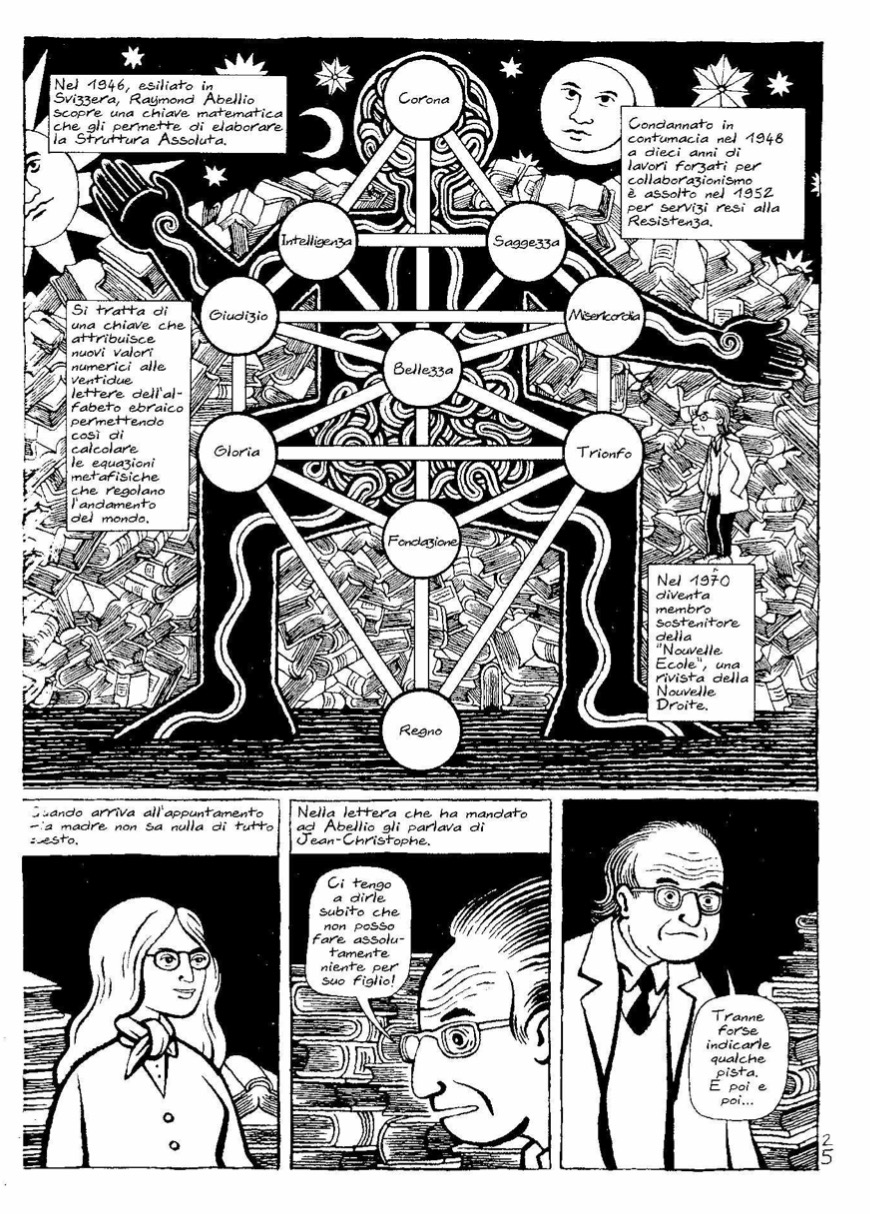

He was very successful at the beginning of his career, then little by little he was forgotten. His esoteric thinking can be found in the La structure absolue, a book that I have read but of which I have not understood anything. If I had to summarize it, I would say that he had found a sort of mathematical formula capable of explaining the workings of the universe, nothing less. I think my mother did not understand anything about that book either, but she did not want to admit it.

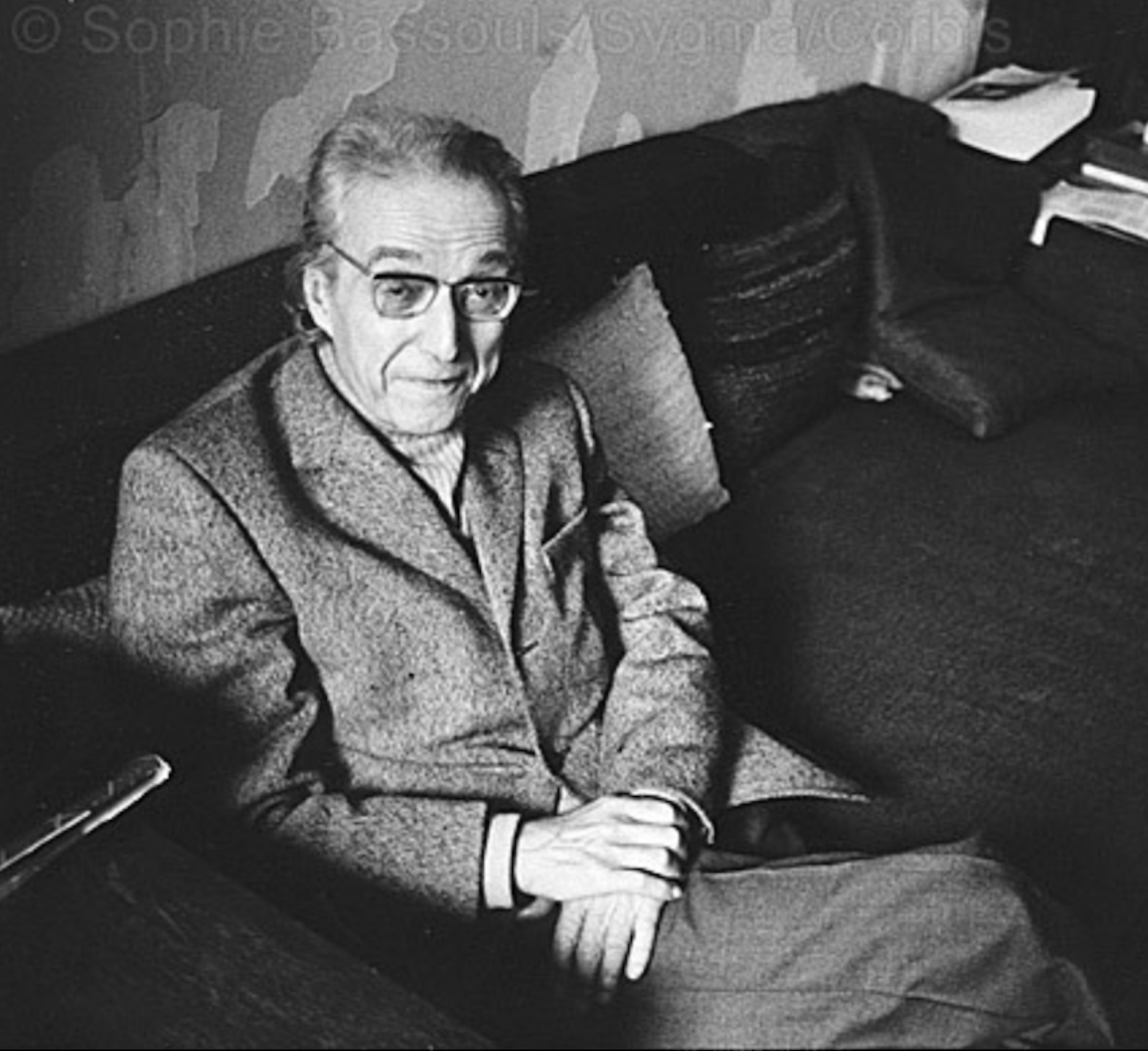

At the time, Abellio was not well known: with books like that, even though Gallimard published him, he touched few people. My mother was one of them. She went to see him and he explained some things to her, gave her big speeches, mostly trying to get her into bed. But, as my mom told me, he had triple lens glasses, he was short, and while he certainly had an intellectual charm he did not possess an erotic charm.

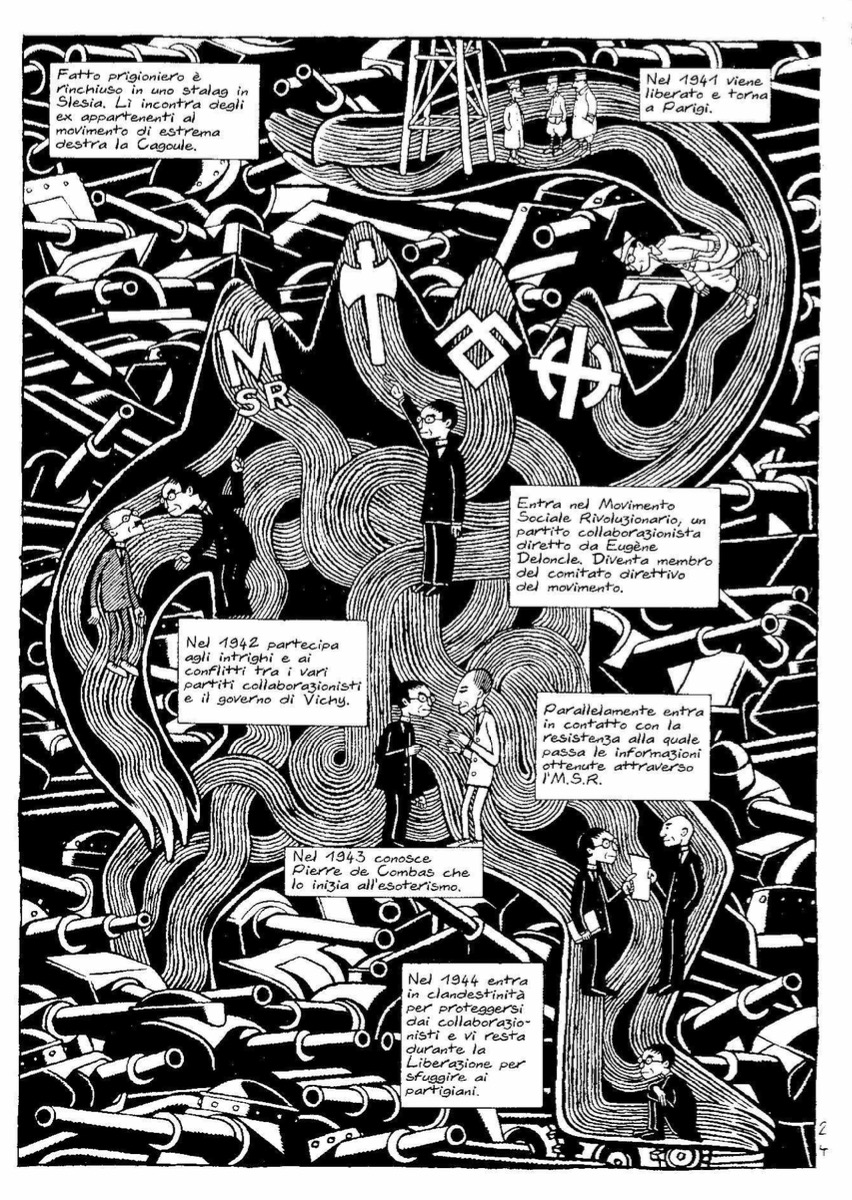

He experienced a period of success during the war when he published his memoirs. In some pages of L'Ascension du Haut Mal I have talked about his winding journey as a collaborationist. He was part of a fascist movement called the revolutionary social movement, which had strongly anti-Semitic ideas. So my mother, who has always been interested in Jewish culture, the only time she managed to meet an intellectual she found one of extreme right thinking. It is a bit sad, but she did not know this at the time. And after the war, Abellio tried to pass himself off as a partisan, like many others.

Emilio Varrà: This speech you are giving is also, paradoxically, a lesson on how you tell stories. And you could tell another 700,000 stories about L'Ascension du Haut Mal but I have some questions instead. Let's start with the topic of minorities. Both in L'Ascension du Haut Mal and Les incidents de la nuit you talk a lot about your relationship with Jewish culture: did your mother influence you?

David B. Actually, my mom was never interested in the Jewish religion. She took from Jewish culture what she was interested in: she saw Jews as intellectual people, who came from Paris to bring culture, and then there were those kids she liked on the bridge...

Emilio Varrà So they represented a possibility of cultural and social redemption.

David B Yes, she was the daughter of a farmer and a teacher, she was passionate about books but she was the only one reading in the village, the other farmers had no desire to learn.

Emilio Varrà But this relationship is your mother's, then there is your own relationship with Jewish culture.

David B Yes, but it is still her who passed it on to me. She was interested in Jewish intellectuals, in writers, not in mystics. She gave me books, she pushed me to read. She always told me: "A good writer must either be homosexual or Jewish", so for her Marcel Proust was the greatest author in the world. She saw that I was interested in the fantastic and she gave me books by Isaac Bashevis Singer, Gustav Meyrink, the author of The Golem (who was not Jewish, although at the time it was thought he was) and other authors, like Bruno Schulz. So I became interested in Jewish literature through the fantastic, and in the end I did not read Marcel Proust but I read Bruno Schulz and from there I moved on to Jewish mysticism.

Emilio Varrà If I think about your work, it seems to me that the relationship between the individual, the community and minorities - three things that don't always fit together well - is a recurrent theme. What do you think about that?

David B It's true, I have always been interested in history, in religion, in esotericism, in heretics, in the slums of cities and therefore in cultural minorities.

Emilio Varrà Also on the autobiographical side, the story that you lived with your family, and that you tell in L'Ascension du Haut Mal, has created a separation.

David B Yes, when my brother got sick we became a minority, we changed position in society. My brother had become a sick person and we the family members of a sick person. I remember when my brother would have a seizure on the street people would stop and look at him and say, "Who is that, what's wrong with him? He is a madman, a drug addict, he must be put into jail". The reactions he elicited were incredible.

This is why I started this speech by talking about the moment when a minority arrived in my mother's village, a small town in central France where there was nothing. This arrival changed many things for my mother who then passed them on to me and my sister. It is wonderful that she has told us a thousand stories about her life, and that they were all so exciting.

Emilio Varrà Did you already have an ending for L'Ascension du Haut Mal when you started drawing the first spreads?

David B No. For twenty years I thought about doing L'Ascension du Haut Mal and one day, finally, I threw myself into the work. I drew the first page, where I go into the bathroom and see my brother totally transformed by the disease to the point that I no longer recognize him. I knew that that would be the first page and then I continued without thinking about how I would do it, the book came little by little.

As a child I was fascinated by medieval miniatures in which realism and fantastic mix. I also used this mixture a lot. In L'Ascension du Haut Mal, for example, I used the tree of the sefirot to talk about Abellio, who at first was anti-Semitic then used a lot of Jewish spirituality and mysticism to found his esoteric thinking.

Emilio Varrà Can you tell about your book Mon frère et le roi du monde?

David B It is a book based on an exhibition I did at the Anne Barrault gallery in Paris. It consists of 72 portraits, 36 of my brother and 36 of an esoteric character called The King of the World. It comes from the book The King of the World by René Guénon, another French esotericist, and it is a mythical figure who represents the union between the spiritual and the material on Earth. For example, King Arthur or Alexander the Great were "kings of the world", they somehow united heaven and earth.

Emilio Varrà I asked you to talk about this book because I find it very important for two reasons. The first is that I believe the symbolic dimension in your work is not just a way to make the invisible visible but a way of saving one's life. The center of your poetics is the awareness that reality is a fracture, a wound, and that we have to invent ways of mending it while knowing that we will never be able to fix it. In my opinion the stories, the symbols, the myths, the continuous progression of the story then become a way of trying to mend this wound. In this dialogue the relationship between the symbol and the harshness of reality is felt constantly. And the fact of constantly coming back to the portrait of your brother, drawing it in always different ways, is a way of finding forms.

David B I drew all these portraits with different techniques that I do not usually use, I really experimented a lot. By combining these two characters, my brother is the king of the world, I wanted to show my brother's weakness in the face of the other's power.

My brother had great ambitions, he too wanted to be a great novelist, to be known, and the disease really destroyed him, destroyed the creative side of him. Even a character like King Arthur, for example, does not remain the king of the world for life. At one point he falls, he dies in battle. There, I wanted to show the possibility that the king of the world might fall.

It is a bit like my brother had the chance of being the king of the world and for one reason or another he had fallen. We don't know where his illness comes from, the doctors have never been able to explain it to us, there is no reason. As Gotlib once said: "Let them deal with it".

Notes on the contributors

David B.

David B. is among the French cartoonists whose work was most influential for the development of contemporary graphic novel, both in France and abroad. He started his artistic career in 1985 as a screenwriter and designer for magazines such as "Okapi", "À suivre", "Tintin Reporter" et "Chic". In 1990 he assumed an increasingly central role in the comic book scene both as an artist and as one of the co-founder publishing house L'Association (the other being Jean-Christophe Menu, Lewis Trondheim, Matt Konture, Patrice Killoffer, Stanislas and Mokeït).

Through his books and artistic experimentations he built a true blueprint for graphic novel as we know it today. Most of his earlier works from the 90s are published in "Lapin magazine", then collected in the volumes Le Cheval blême (L'Association 1992) and Les Incidents de la nuit (L'Association 1991-2000). From 1996 to 2003 he devoted himself to L'Ascension du Haut Mal (L'Association; Epileptic, Pantheon Books 2002-2005), an autobiographical graphic novel in six volumes who won the Best Screenplay award at the Angoulême International Festival. His artistic contribution to historical and non-fiction comics as well was seminal, as attested by the series Les Meilleurs ennemis (Futuropolis 2011-16), a graphic novel in three volumes exploring the complex relationship between USA and the Middle East, written with French historian Jean-Pierre Filiu.

In 2005 he left L'Association, where he returned in 2011 as a member of the editorial committee. In 2018 he published as a screenwriter the 37th volume of the series Alix (Casterman 2018-2020) with designer Giorgio Albertini.

Emilio Varrà

Emilio Varrà is the president of Hamelin, and one of the organizers of BilBOlbul International Comics Festival. He teaches Children's Literature at the University of Bologna and is a professor at the "Illustration and Comics" course at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna. He wrote several academic publications dedicated to comics and illustration, and he collaborated with magazines such as "Li.B.e.R", "Gli Asini", and "Lo straniero".