Building the Invisible

Emilio Varrà The invisible is part of the creative process: first there is nothing and then there is something. I would like to start from this, and from the memory of some things you have said to me, and which I will now quote simply to introduce the question.

The last time I saw Lorenzo Mattotti, one of the first things he said to me was: "I'm sick of stories! Plots are totally useless because they trap you". I remember when, many years ago, he showed me the preparatory drawings of Ghirlanda and explained how complicated it was to start a comic and how much he felt the weight of it, not only because it is a long process but also because putting the panels in sequence narrows one's field of action.

I also remember that, while working on his exhibition L'intervista for an old edition of the BilBOlbul festival, Manuele Fior said that it was very important for him during the creative process not to know exactly how to proceed.

We started by saying that the creative process is to make visible something that was not there before, but it seems to me that one of the things that unites you is the effort of trying to maintain the invisible even during creation.

How does this constant contrast between constraint and freedom (therefore also between marks on the sheet of paper and the invisible) act in your work?

Lorenzo Mattotti For me, drawing means concretizing the invisible. Any drawing I make is an effort to put on paper something that I feel or recognize and which, once thrown on the sheet of paper, becomes something. To draw is to build the invisible.

One of the most difficult things in comics, for example, is to concretize smell and music. In fact, I remember that sometimes, when we were doing stories with my scriptwriter friends, I said to put in the captions the smells that the character could smell.

But let's go back to when I was talking to you about Ghirlanda: at the time I was feeling the clash with the language of comics. I had been trying for a long time, in my head, to build a story based on the improvised drawings of my notebooks, drawings I call "fragile line" that are improvised on the spot, flashes, visions that are born on paper, flickering, disarmed.

When I took it upon myself to build a sequential narrative that had this extremely sensitive quality, I started having to follow conventions, and a certain character who had started out with an incredible fragility of drawing required building. Just the fact of having to draw it many times transforms the line into a structure. The light marks that previously evoked a landscape becomes, when you begin to write a story, a road, or a forest ... Everything is trapped in the convention of language.

This convention allowed me to communicate to the reader, but at the same time those drawings that were fragile, emotional, full of invisible evocations were impoverished. In narrating the invisible, sometimes the story gave me an itinerary, because the reader understood a drawing or a sequence that could not be explained without words.

But there are things that can only be explained with lines and images, and that is where every now and then I have tried to arrive at, that is, the maximum power of the mystery of drawing, which is after all the concretization of a mystery that does not even need to be revealed. This is why I say that our work is a continuous attempt to give shape to the invisible.

Manuele Fior I am excited to have this talk because it is the first time that I speak with Lorenzo and I will quote his work many times, not out of flattery but because he represented so much for me.

So, the invisible: perhaps due to my past as an assistant to archaeologists ( I did many jobs before becoming a cartoonist) the invisible is linked to unearthing things. I have the impression that there are images and core narratives that are already present but cannot be seen; the artist begins to scrabble, then he glimpses a small detail and goes on like this, like an archaeologist who does not really know what he will be facing.

I remember that once in Alexandria, Egypt, I was sitting on something that was pricking my bottom; at a certain point we began to dig around in that area and found the skeleton of a gentleman buried there in the 1700s. Even with drawings, this is often the case.

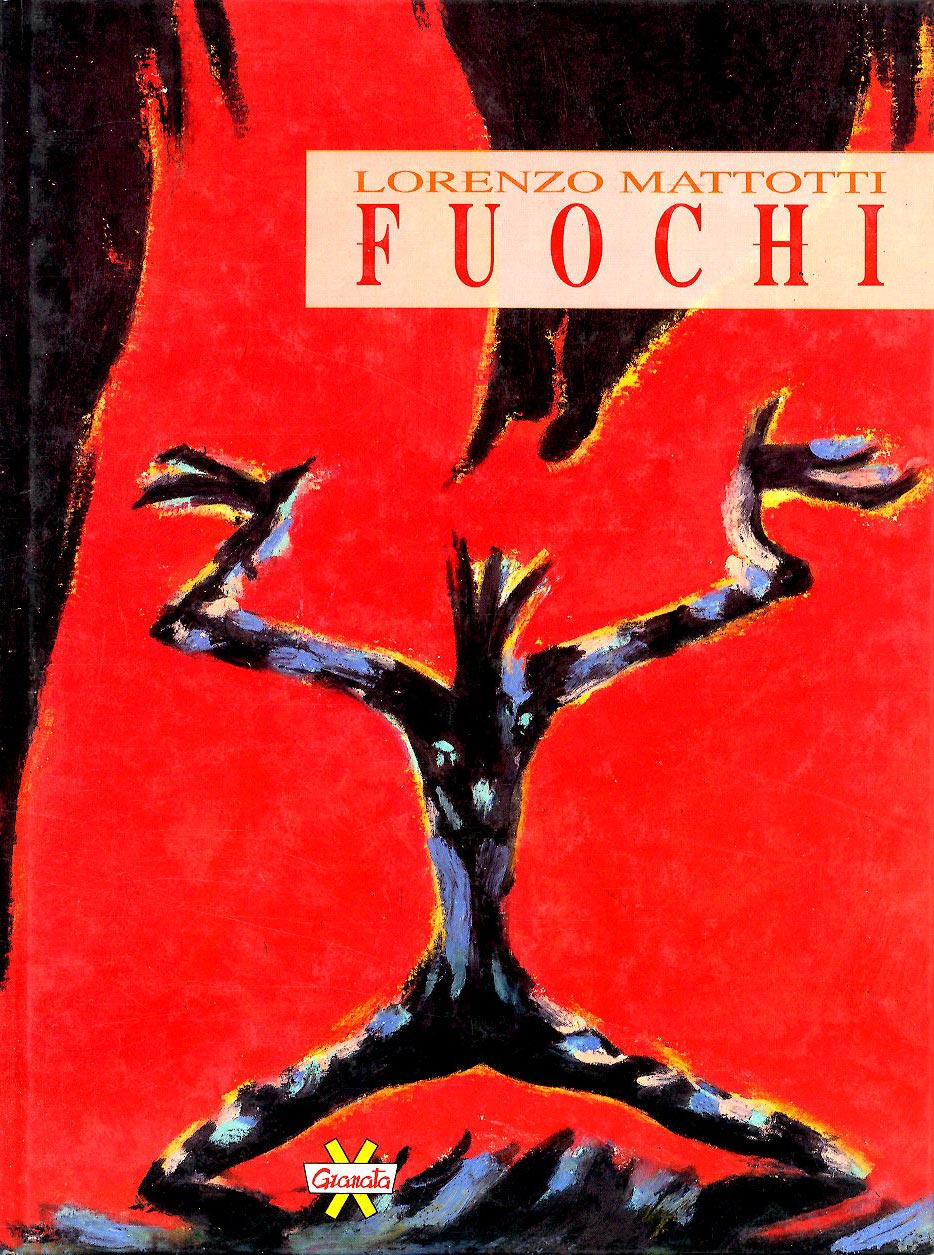

I will quote Mattotti for the first time now: once I asked him how he had worked on Fuochi and he said to me: "Well, I started with very strong images and I built bridges between one image and another". This for me is making comics: to make a true story you don't have to know what it is about; you will know that in the end, maybe, because even after the end a story is always equivocal, always interpretable.

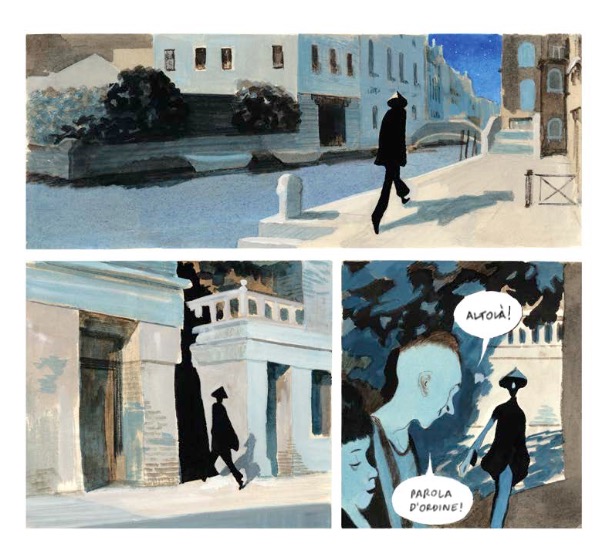

In the last comic I did, Celestia, I started as I always do from the first page knowing only that I wanted to work around the topic of the island where we are today, Venice. I had taken possession of it, I began traveling, reading everything I could, all the comics that had been made about Venice including that of Lorenzo Mattotti, Scavando nell'acqua.

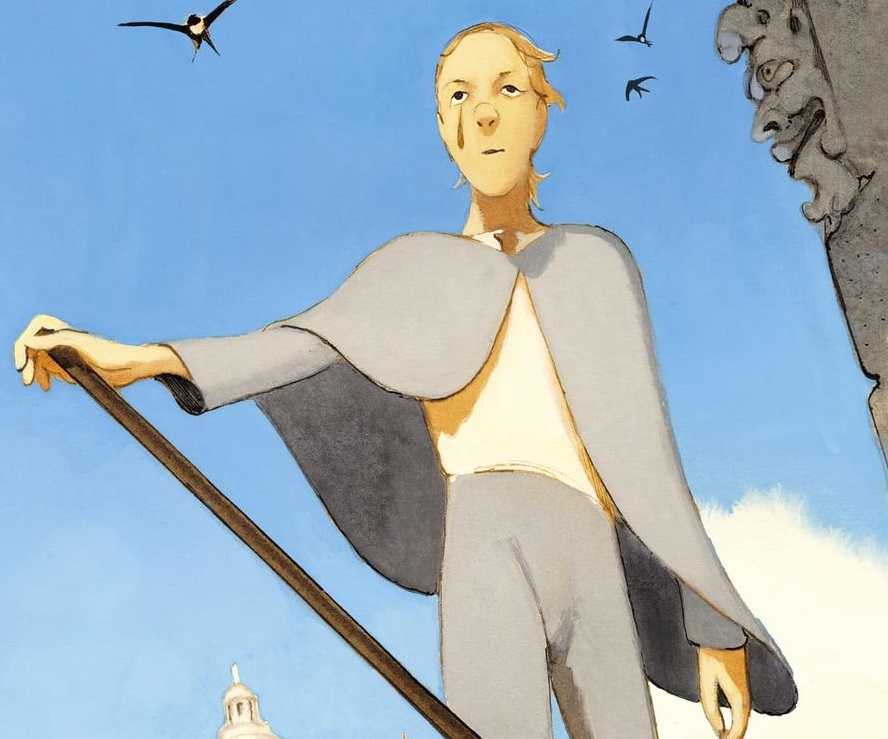

In the first panel I drew a black silhouette: I needed a character who would open the story. Then, as soon as I turned him around in the next page so that he was looking at me, I stared him in the face and, I don't know why, I put a tear on his face. As soon as I drew the tear, I felt a snap and thought of Pierrot: on the one hand as a character in the Commedia dell'arte, a sort of melancholy poet but also a murderer; on the other hand, though, I was also thinking about a memory from my childhood.

As a child I always forgot everything! Once I even forgot the school carnival party, so my mother, in order not to make me go without a costume, dressed me in white, put a black cap on my head, drew a tear on my face and said: "You are Pierrot".This character, therefore, wasn't indifferent to me right from the beginning.

This is how the invisible is revealed and asks to be revealed. The process of unveiling it is an enchantment, it is an ability that we have, and which unfortunately we censor a little as adults - the ability to be entranced in front of images, music, a landscape, even in front of a person. This process of unveiling is a wonderful thing, in the sense that it arouses wonder and it is for this feeling that the whole gestation of the book is endured.

Because in order to make comics, as Lorenzo rightly said, one must acquire a language to be able to transmit this enchantment to others, otherwise it is like telling a dream. Perhaps the most appropriate definition is precisely the unearthing of something that had always been present but that we did not know was there, and this gives a great feeling of surprise.

Emilio Varrà You both spoke of revelation, enchantment, wonder… We are then in an impalpable territory, but there is also the solidity of the moving body, of the drawing being made. So I ask you to zoom in on the act of drawing: what is the revelation there? Which is the discovery and which is the failure?

Manuele Fior This question has to do with the basis of comic language that Dominique Goblet spoke of. The problem with comics is that they are made up of two very simple things: drawings and text. The sum of these two things, however, produces something more than a talking figurine.

It is like an antenna, and whoever draws receives a message that is sometimes disturbed and sometimes very clear. We must rely on this message, develop what is around it; the technique is a producer of contents.

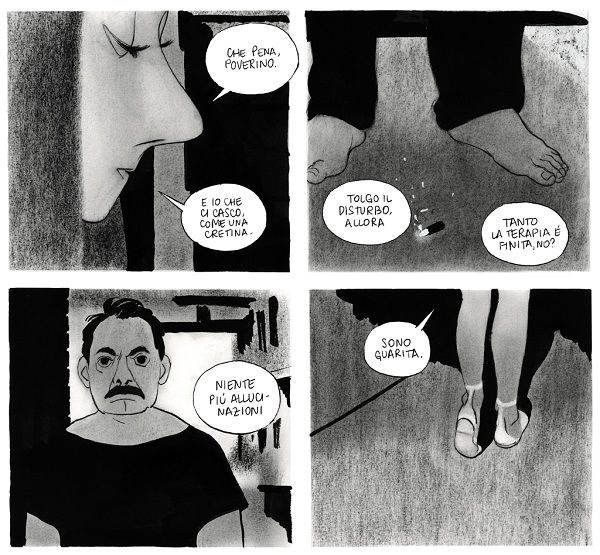

For example, when I did L'intervista I very quickly drew night skies in which a cloud would appear with the blow of an eraser: this is the most absolute concreteness, it is technique showing you where to go, what to explore.

Lorenzo Mattotti One of the big problems I have when I have to draw stories in color is that by drawing the sketches in pencil first, I have the anguish that a certain expression, for example, will end up being covered by color. Sometimes I have photocopied or scanned my books in black and white!

The color in your head, which is invisible, finally blooms when you see it on paper, and it does not always come out the way you expected. What you imagined as blue has become half green and half orange, what you had in your head is actually something else.

We have emotions, music and drawings inside, but the mechanism that makes them real is not direct. You think you are doing one thing and then another comes, you have to question it, look for side routes, go back until finally what you had inside appears. Because you have it, but it is shapeless, it is an emotion. This is the magic of working this way. Improvisation has always transported me, grafting a moment of magic within a structured code... There is an energy that you can only find in improvisation.

And readers understand it, communication passes through this energy. I am convinced that if I am enchanted, the reader will also be enchanted, and if I am bored the reader will also be bored. I have more and more confidence in the improvised image, I believe that there lies the core of the mystery, of the charm of drawing, of the image speaking with the language of images.

Emilio Varrà In your stories you both often tell of characters who are in search of something. This has to do with invisibility because the future has to do with invisibility. What are your characters looking for?

Manuele Fior I don't know where my characters are going... But it is certainly the reflection of a kind of restlessness that made me (and Lorenzo too) travel. My dad is a former air force pilot and for this reason I never lived in the same place for more than two years; I did elementary school in two different schools... It was very easy to understand but it took me psychotherapy to figure it out: the place where I have lived the longest is Paris, not Italy!

So I think this is a litmus test of my life. After traveling a lot with my family, I left Venice because I could not take it anymore and I was afraid of ending up doing a job in a technical studio. I had my family in hot pursuit of me, so I fled to Berlin in 1998 and returned to live in Venice a year ago, after being away for twenty-two years, first in Berlin, then in Norway, and in Paris.

In my opinion comics, being adaptable, eat everything that happens to you while you do them. Generally it takes a few years to finish a graphic novel, and in the meantime maybe you have changed your life, you have had a child, all sorts of things have happened to you, you are no longer the same person you were when you started. The graphic novel is the trace of this movement.

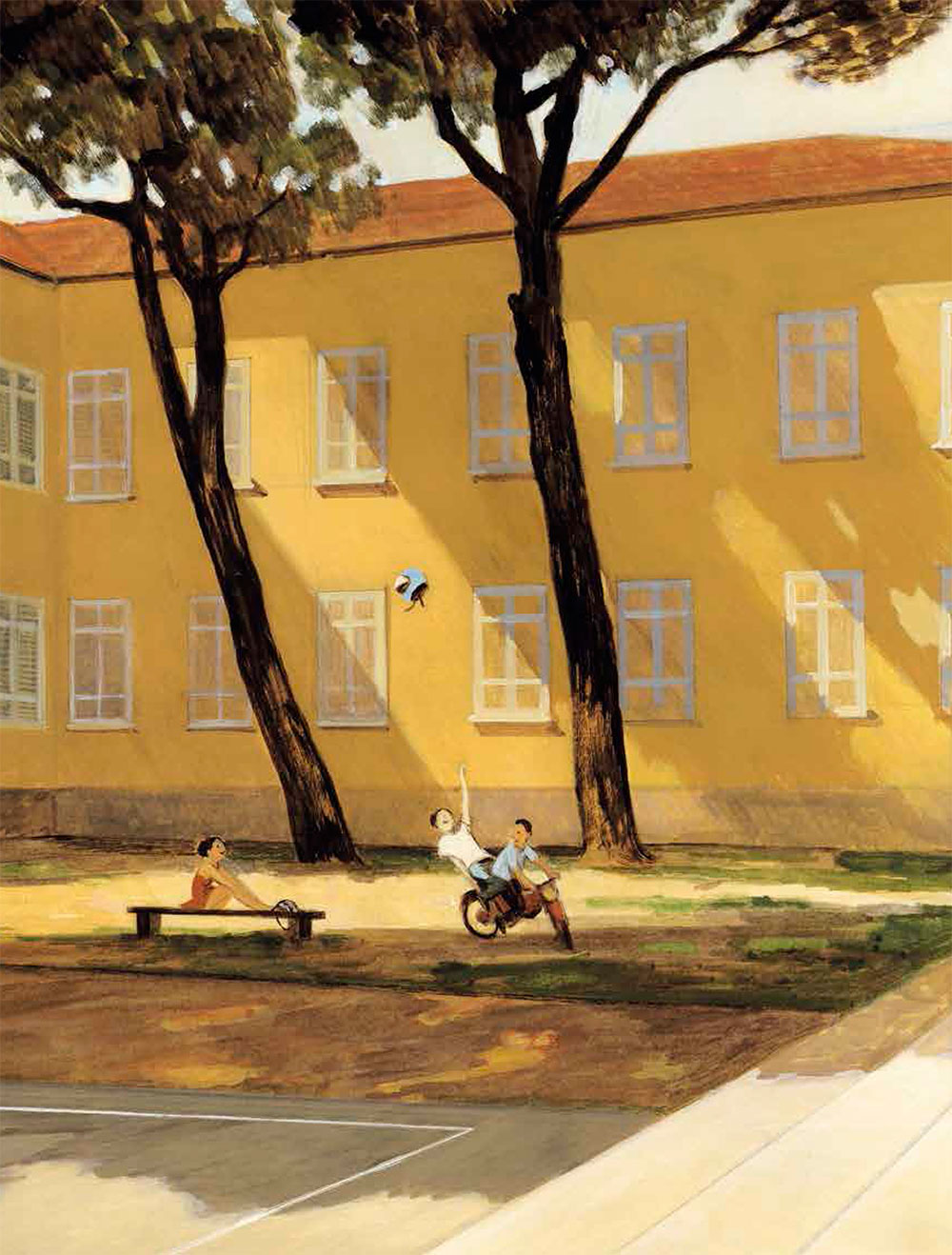

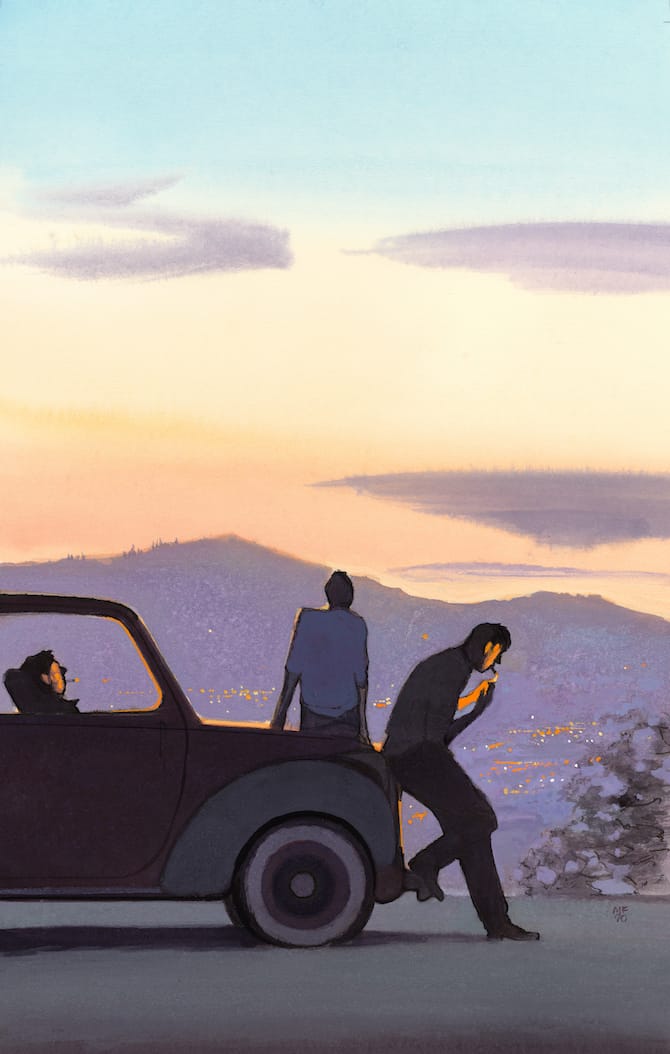

I honestly don't know what my characters are looking for, in every story it is something different. In 5000 km al secondo they simply get lost in the world, they leave without knowing where to go, without knowing if they can call themselves Italian, French...

When I was working on that comic, at the end of the Nineties, it was very easy for people to travel, while now it feels like the world is shrinking. Everything was opening up then, but now this bubble is closing. When I heard that after Brexit UK universities would no longer accept students who did not know English, I thought that I had never gone to a country whose language I already knew.

Adventure, a term that I love very much and which has long been looked down on, is actually the adventure of our lives, which sooner or later will have to end. It has temporary, large or measurable movements and the characters are part of this movement - they win, they lose, they fall in love, they hurt each other. I think it is the closest thing to a character's life that you can instill in a small paper sketch.

Lorenzo Mattotti I very much agree. Among other things, we have had similar experiences: my father was also in the military and we spent four years in one city, then four years in another... I reflected on the fact that also for me Paris is the city where I have lived the most.

When you have a life like this, you get used to change. The idea of staying in a city for more than four or five years makes me anxious, the idea of staying in one place for so long anguishes me. I probably poured this aspect of mine into comics: I cannot always do the same thing, I have to question everything otherwise I become a professional in comics, an illustrator of children's books or a director of animated films. Instead I want to find adventure every time, and question myself.

Back to your question about movement. I add change. In my stories I have always tried to record the changing of my characters; for them the story must be an experience and the same goes for me as a designer and narrator. Time passes and the drawings change. All my comic stories have become my experiences.

If you look at Fuochi, at the beginning the character is in a certain way and little by little he transforms.

My stories are always in motion, and in the process of change they are also a metamorphosis. Perhaps unconsciously I always dream of change, even though as you get older you realize that nothing ever really changes... But the attempt to change is the engine that keeps me drawing, makes me destroy the mannerisms which I hate because they mean that I am not in motion. And Manuele is right in saying that the story absorbs all of this. Stories change, they are objects in continuous motion.

Emilio Varrà

How does this process change when you work on a single image? The temporality changes, and the relationship with invisibility changes, in the sense that if the comic is also an act of filling up empty spaces between one drawing and another, in illustration or in a single image the invisible speaks. How does the relationship change between what one sees and what one decides not to show in illustration?

Manuele Fior

I do not consider myself a good illustrator, perhaps not even a good cartoonist. But I am a bit better as a cartoonist than as an illustrator, in the sense that Lorenzo Mattotti is capable, like other great illustrators, of enclosing a world in a drawing, while I have a lot of difficulty doing this and it always seems to me that I have to explain it in some way, put something in front of and behind that single image... Basically to make a comic! But I am absolutely seduced by the ability some artists have to condense everything into single images. Böcklin's painting or an illustration by Kubin function as generators of narrative universes, for example.

What I do for work with illustrations does not matter very much to me. The most important things in single illustrations are those that hardly anyone notices but that open a kind of "bubble", things that are not particularly beautiful or significant but which point into a direction, as if someone with a telescope had sighted an island.

There is a beautiful four-part documentary about Miyazaki that explains this concept. It is about Ponyo, one of his most famous films. There he is, suffering like an animal because he is not able to start, the whole studio swearing after him because they are late, but he cannot begin because he doesn't have an image, and at a certain point he starts messing with paint, he finishes a drawing, he looks at it and says: "There, we've got the film!".

I have a very instrumental relationship with the image: I make it, I put it away in a drawer and I need it to explode into the whole story.

Dora from L'intervista, for example, was born from a profile, from a sketch that I had framed for personal purposes, because when I drew that profile, that nose, it was as if I had always known it, as if I had already seen it. This is the relationship I have with single images: they are comic book detonators.

Lorenzo Mattotti At first, when they started asking me for illustrations for the press, it felt like an epiphany. I came from Fuochi, where each panel was a potential story, a concentrate of energy and narration. To make one panel I would spend a week thinking, so when they asked me for a single drawing it seemed very easy. Illustration has been oxygen for me, because it has allowed me to take advantage of my ability to draw quickly and make still images that had to be strong but did not need all the design complexity associated with a sequential story.

Then it became more complicated because, upon reflection, there are free illustrations, illustrations for posters or covers, or for literary novels, and each one has its own language.

With experience you learn to create an illustration that works like a closed narrative, in which the eye continues to turn ... There is a big difference, however, between illustration and free image: an illustration exists in relation to something, it has a function, while a free image is just for you. I have sometimes used free images for magazine covers, but illustration follows a very precise logic, it pushes us to focus on the internal tension of the image and on a general evocative power.

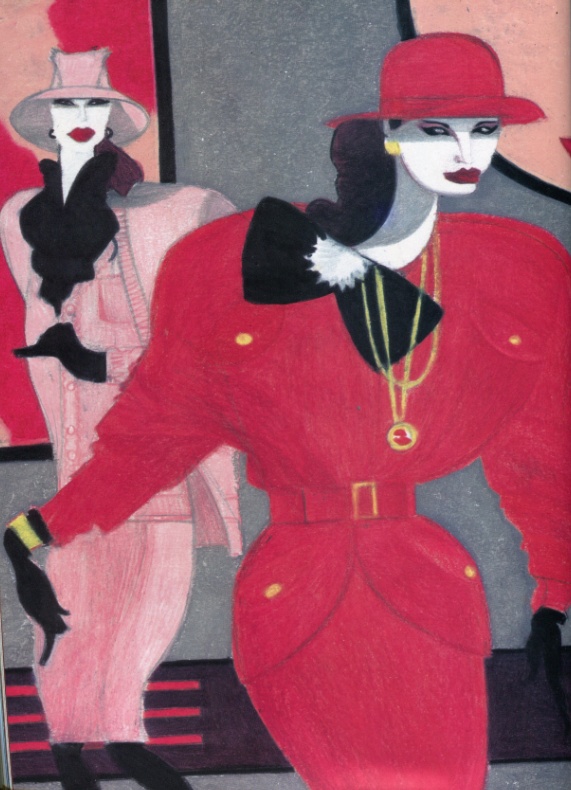

I remember that, concerning my fashion illustrations, a director of various magazines said: "Mattotti doesn't do mannequins, he continues to make living characters". After all, if you have the nature of a storyteller, a story comes out in any situation. There are illustrators who do not tell any, whose charm lies elsewhere; I feel them distant, I feel that they do not create characters but shapes. A bit like certain painters who follow a rational, cold, detached logic. Bacon for example, and all of modernism with their idea of an image that must completely detach itself from narrative. Even though not even those painters succeeded completely, because every image tells a story.

Notes on the contributors

Manuele Fior

Manuele Fior is one of the most relevant Italian contemporary comic book artists, and one of the most celebrated and recognized abroad as well. With his graphic novel 5000 km al secondo (Coconino Press 2010) he won the Fauve d'Or Award as Best Album at the Angoulême International Festival in 2011. Among his other publications: Rosso Oltremare (Coconino Press 2006); La signorina Else (Coconino Press 2009) based on the novel of the same name by Arthur Schnitzler; L'intervista (Coconino Press 2013); Le variazioni d'Orsay (Coconino Press - Fandango 2015); the short story collection I giorni della merla (Coconino Press - Fandango 2016). His latest graphic novel, released in 2019 by Oblomov Edizioni, is Celestia, a science-fiction tale in two volumes set in a futuristic city inspired by Venice, in which Fior uses his visual and narrative imagination to envision the future of humanity.

His graphic novels have been translated all over the world and international editions have been published by Atrabile and Delcourt (France), avant-verlag (Germany), Jippi Forlag (Norway), Sins Entido (Spain), Fantagraphics Books (USA).

Alongside making comics, he works as an illustrator for magazines such as "The New Yorker", "Vanity Fair", "La Repubblica", "Le Monde", and "Il Sole 24 Ore" and for some of the most important Italian publishing houses.

Lorenzo Mattotti

Lorenzo Mattotti is perhaps the most known and globally celebrated contemporary Italian comic author and illustrator, thanks to the undeniable impact of his work, ranging from different artistic forms: comics, illustration, children's literature, animation, cinema, painting. He has been an acclaimed artist since the 1970s, with works such as his illustrations for Le avventure di Huckleberry Finn (Ottaviani 1976) and stories like Alice brum brum (Ottaviani 1977) and Incidenti (Hazard 1996), published in the supplement of the Italian alternative magazine "Alter alter". His ever-transforming visual style has paved the way for contemporary comics, making him one of the forerunners of graphic novel at a time when no one had ever even heard of "graphic novel" yet. His production is vast and diverse; among his most important publications: Il signor Spartaco (Milano Libri 1982); his masterpiece Fuochi (Dolce Vita 1988), historically considered a trailblazer for an unprecedented way of making comics; L'uomo alla finestra (with Lilia Ambrosi, Feltrinelli 1992); Stigmate (with Claudio Piersanti, Einaudi 1999, ); Jekyll & Hyde (Einaudi 2022, written by Jerry Kramsky); Chimera (Coconino Press 2006); Ghirlanda (#logosedizioni 2017, written by Jerry Kramsky). Skilled manipulator of color and lines and tireless experimenter, he collaborated with all the most relevant independent Italian magazines such as "Frigidaire", "linus" and "Il Corriere dei Piccoli". In 1983 he co-founded the Valvoline group in Bologna with other avant-garde artists, marking a turning point in comics. He also drew covers for magazines such as "The New Yorker", "Vanity Fair" and "Glamour", advertising campaigns, and children's books. He has worked in cinema and animation alongside directors such as Michelangelo Antonioni, Steven Soderbergh and Wong Kar-Wai. In 2019 he directed the animated film La famosa invasione degli orsi in Sicilia from Dino Buzzati's novel. His works have been exhibited all over the world.

Emilio Varrà

Emilio Varrà is the president of Hamelin, and one of the organizers of BilBOlbul International Comics Festival. He teaches Children's Literature at the University of Bologna and is a professor at the "Illustration and Comics" course at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna. He wrote several academic publications dedicated to comics and illustration, and he collaborated with magazines such as "Li.B.e.R", "Gli Asini", and "Lo straniero".