A third meaning

Ilaria Tontardini Observing the works of Dominique Goblet and Stefano Ricci, one can see a strategy for expressing the invisible made up of fragments placed side by side, a way of putting things into relation using fragments that break with the linear nature of time. This confuses the reader, because the full picture of the story becomes apparent only at the end. So my question for you is: how does piecing together fragments of history and time function in your work? And why did you choose to work on this break in linear time?

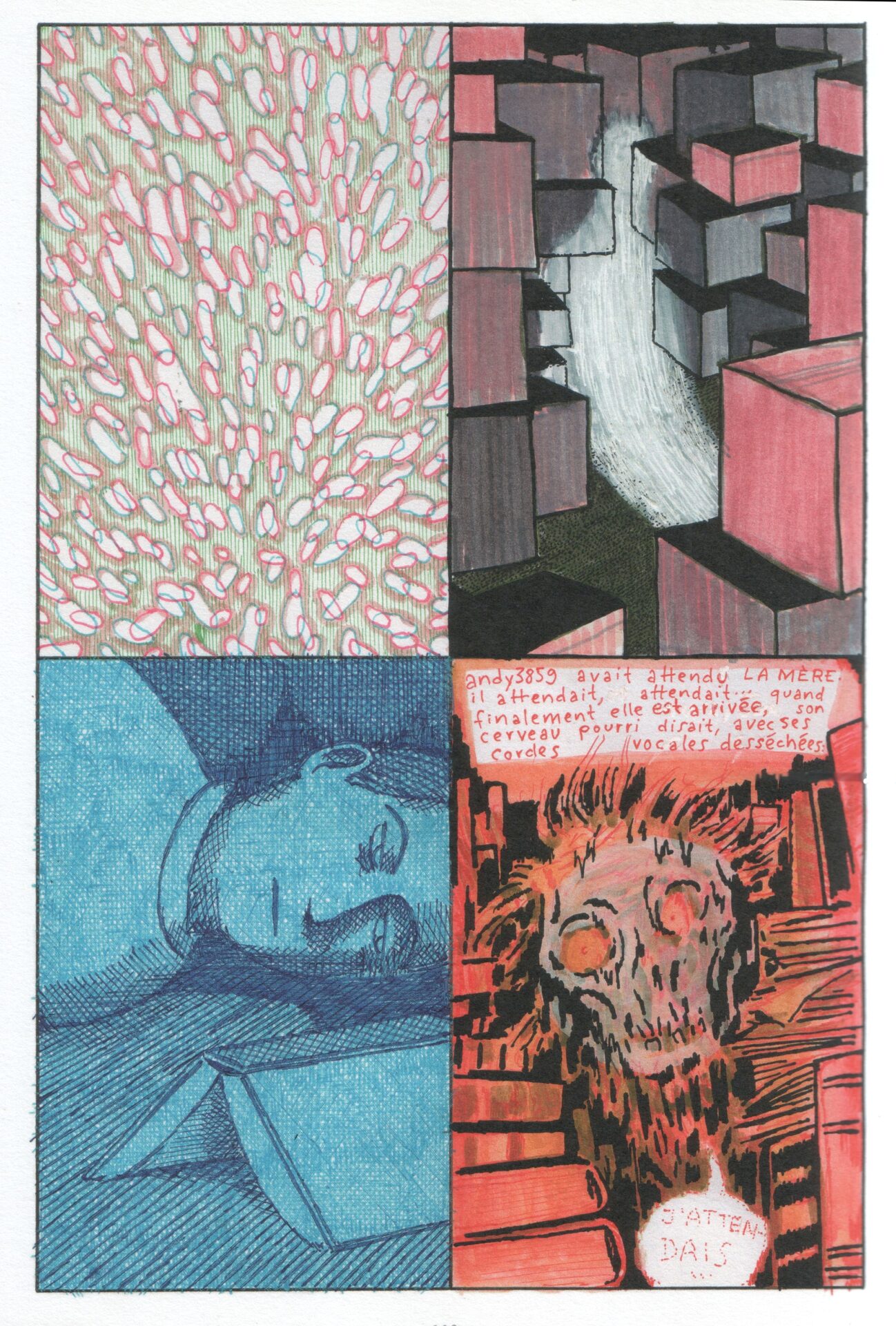

Dominique Goblet Comics is a medium that uses text and images, as you all know, but what is interesting is that the interplay of text and images produces two levels of interpretation. The image says one thing, the text says another and the relationship between these two elements produces a third meaning.

When you write, as a cartoonist, you do not write a story which is then cut or illustrated, but you write text and image at the same time: this is the basis.

In my artistic career I have often felt the need to deal with brutal themes, but it is impossible for me to face brutality head on, so I always try to find secondary ways of building my stories. I am especially interested in extracting beauty from brutality, grasping its element of tenderness. When a story is very crude, I try to go around its core to bring out a different perspective, to show how the mechanism of a violent interaction can go all the way around and arrive at empathy.

The comic is a perfect medium for this type of work, due to the double text-image axis that allows you to heighten the tension by combining a very violent text and an image that uses a code of profound sweetness. For example, logic would have it that if I write a story about World War I will have to use earth tones, draw rainy and gloomy atmospheres. On the contrary, if I use soft colors, watercolors, I produce a short circuit of meaning and this will be what suggests violence.

Stefano Ricci Yesterday I visited the Open-End exhibition here in Venice by Marlene Dumas and I saw a painting that I did not know, called The Bride. It is the image of a woman with a white, almost transparent veil covering her face. She made me think of my mother's best friend, a cloistered nun. Her convent was in the center of Bologna, there was a garden surrounded by very high walls, an independent space.

We used to visit her with my mother and my brother. We would enter a small room, go through a door and sit on a small bench. My mother would take a few steps and approach a window in the center of the room that had iron bars. To the right of this window there was a wheel, let's say a kind of barrel where my mother would throw small gifts for her friend. The barrel turned and from the opposite side of the adjoining room, behind bars, a door would open and my mother's friend would come in. She had a transparent black veil on her face, you could see her and also could not.

Of all the women I met who were close to my mother she was, in my memory, the most beautiful. The two of them talked very quietly, they would exchange a small packet of paper on the wheel, while my brother and I waited and waited. Over time I have tried many times to draw her veiled face, that transparency which is also what we look for when we try to draw skin-tones; a living thing that in a certain way is in relation with the truth. When I drew and wrote my book Mia madre si chiama Loredana I went into that room again, I tried to draw it and despite all my attempts I just could not.

I asked my mother why her friend wore a veil and she answered: What veil?

Dominique Goblet I would also say that in my artistic journey there are two ways to make a book: I can know the axis of the project, so I am able to write it before getting to the drawing; and there are projects that gradually emerge from drawing, which are the result of a connection with the unconscious. This second modality is perturbing, it requires you to listen to your drawings and ignore a part of yourself that suddenly emerges like a flash.

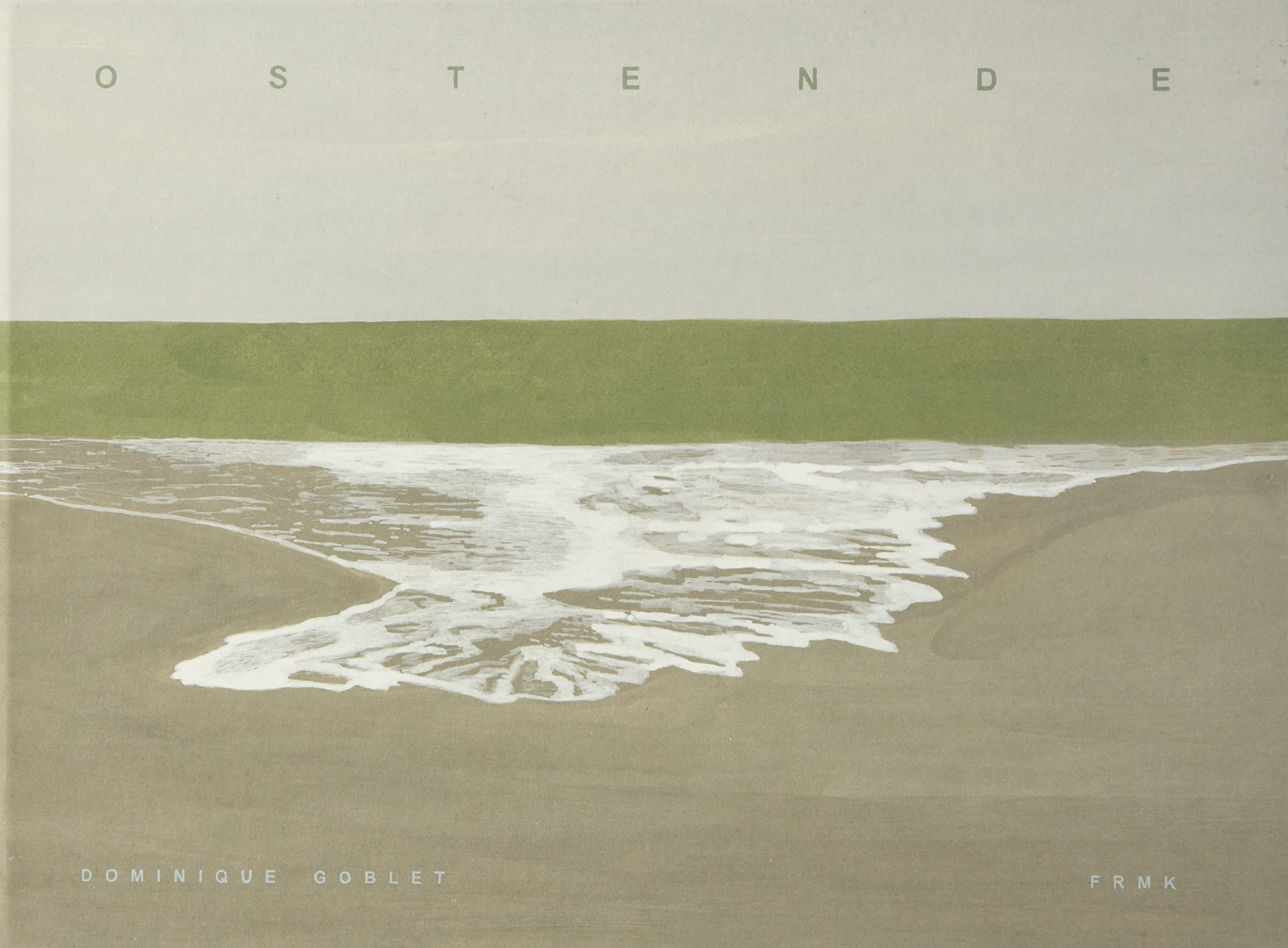

This was the case with my latest project, Ostende. During the Covid period I was at the seaside, in Ostende, Belgium. I was going through a rather complicated period of my life. I was dealing with a very painful separation, but I did not want to talk about it with anyone.

I felt the need to start working on a new personal project, testing myself with new techniques. I really like to start working with new techniques to get closer to projects I have never done before, because I think knowing how to produce something with an unknown instrument brings something pure and personal into the work. To produce a truly effective work, it is essential that artist know how to put themselves into a difficult position, that they know how to work with a 60% handicap and a 40% of competence.

The real challenge is learning to love your own difficulties. And not just love them, but try to make them your own and always show them off. It is not a given that something that has never been seen before will come out of it, but certainly something will emerge from the heart's most intimate part, like an erupting volcano. When working with self-imposed limitations, it becomes automatic to ask yourself the reason for what you are doing.

In Ostende's case, what does it mean to draw a landscape today? The first question I asked myself as soon as I arrived at the sea was: what happens to me when I arrive in front of the sea? Ostende's sea is a sea that does not appear immediately, to see it you have to climb a sand dune and each time on the other side there is a different landscape, with different colors, and this change produces in me emotions related to smells, feelings, colors.

I don't want to reproduce it exactly, I want to give the drawing the impact that the sea has each time, depending on the emotion with which one reads it.

The sea is different there, it is not a vacation spot, it is not the Mediterranean. It is made up of unique colors, not only the classic blues but many grays and browns, it brings with it many emotions that are not easily translated.

When I started drawing the sea, being a purely frontal landscape, I decided to eliminate blue both from the sky and from the water, thus giving it its own identity and feel.

Ilaria Tontardini I find the idea of spatial order and disorder that is created by the interplay of text and image in your work very interesting. In particular, if I think of Stefano Ricci's books, they always contain parallel stories that cross and overlap. It is like weaving, only at the end you can see the overall texture. What is your creative process?

Stefano Ricci I grew up in a working-class neighborhood, in a working-class family in Bologna. There was a courtyard: it was long and without grass, with acacia trees (poor things, almost petrified), and there were cars. People, families did not change cars often, so they took care of them. In the evening, all the people who had a car - and there was a very long view of them, there must have been at least sixteen - covered it with gray plastic sheets fastened with rubber bands. All the vehicles, which had different shapes, became gray ghosts in the evening; you couldn't even see the wheels. My brother and I went to bed, and in the courtyard there were those sleeping ghosts. I have tried to draw them many times, but have never succeeded.

One day in the studio, looking for paper, I pulled out a drawing of a car, a Ford Capri owned by the father of some of our friends who lived on the ground floor. The drawing wasn't anything, it was just this Ford Capri. So I took some transparent white tempera paint and covered it, it took me a few minutes.

A few days later I met a person, his name is Gagliardi, he is my age and draws identikits very well, he works at the police station. I had tried to meet him because I had read about him regarding the Uno Bianca murder. This man had drawn two portraits, two identikits that were the result of some oral descriptions; because this is the enigma that preoccupied me on the question of identikits, the oral description of a face that becomes an image.

These two portraits / identikits had been hung in the hallway at the police station. The Savi brothers, the two murderers, sometimes robbed small suburban banks and the first thing they would do was shoot the surveillance cameras.

In a small branch, in Budrio I believe, they had fired but the video camera had not broken; the bank manager had noticed that the camera had continued recording, so he printed the photos of the Savi brothers, he went to the Bologna police headquarters and asked to meet with a magistrate.

While waiting for the magistrate, he saw the two identikits, in front of which many policemen had passed for several years, and he recognized the two Savi brothers and understood. He went home and realized that the matter was very serious.

I had read about this in some articles and for this reason I wanted to meet Gagliardi, ask him some questions about the drawing, about the face, about being permeated by an oral description to execute an image, and also about the mystery of not falling into the temptation of making a beautiful drawing, but to be solely a tool that makes a person's invisibility visible.

When I was finally able to meet him at the police station, I did not know where to start. He was very kind, I asked him: "How would you define what you can do? What are you capable of doing with drawing? ".

He thought about it for a long time and told me: "Look, I think I can draw at least 7000 different cheekbones".

And I thought that if you can draw them it means that you can see them. You can see 7000 different cheekbones, you can see the transparency, the face under the veil of the skin, you can recognize these differences, you can see the uniqueness of this beauty.

I asked him: "Could you please draw some?". And he said: "Sure!". He took paper, a pencil, and began to make these signs like an alphabet: one, two, three, four ... When we reached thirty, I was enchanted, and I said to him: "I believe you, I give up".

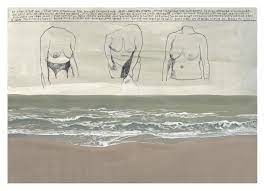

Ilaria Tontardini The visible and the invisible, the way an image becomes a story, lead me to another question that has to do with the human body. In both your works the body is the main character, albeit in very different ways. In Stefano Ricci's books the body is an instrument of memory; in those of Dominique Goblet the body is exposed in its most erotic, sensual side, it is a real presence that catalyzes narration. How important is the representation of the body to you?

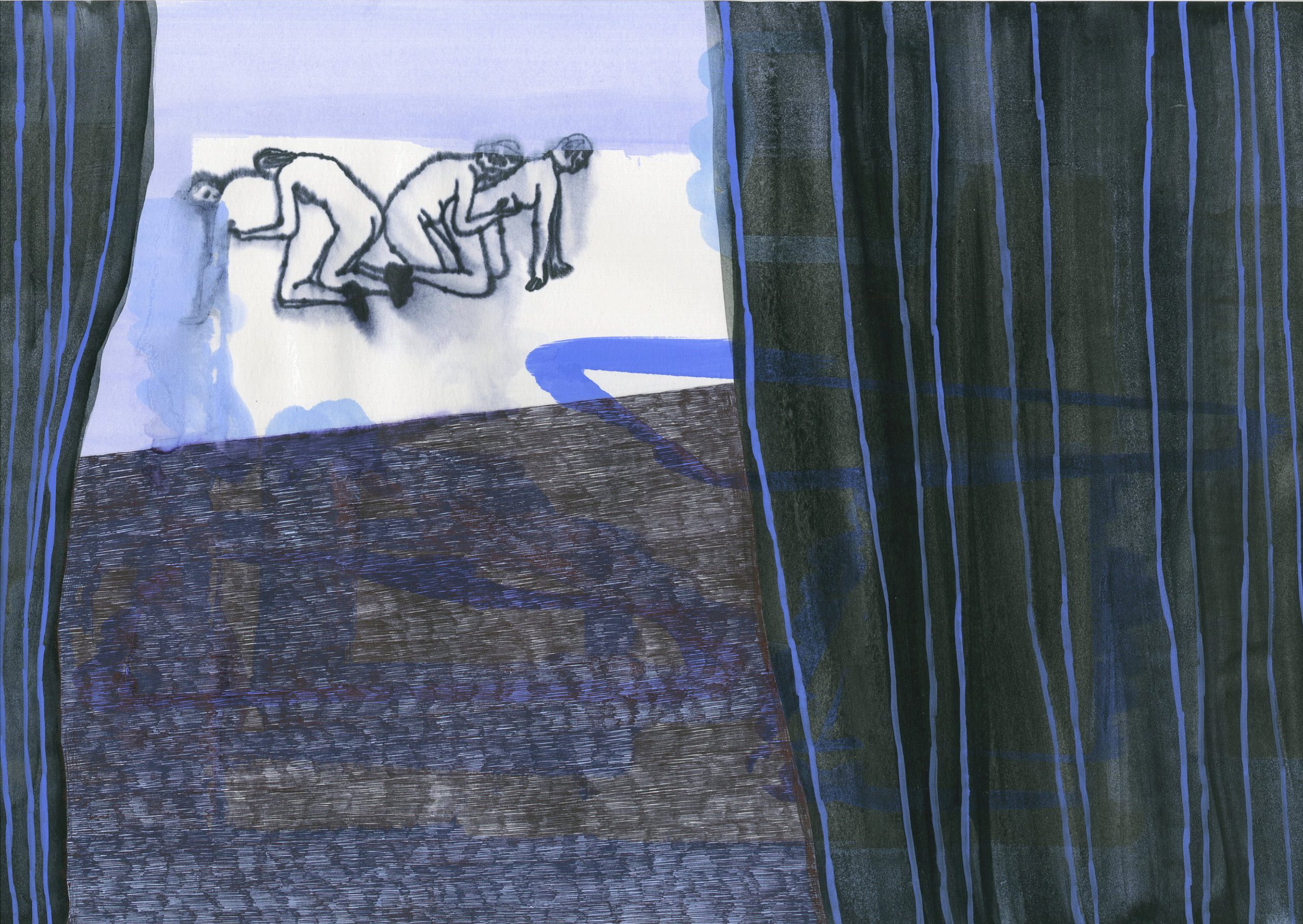

Dominique Goblet If we talk about graphic novels, whether fictional or autobiographical, the characters are one of the engines of comics. In my last work in particular, Ostende, I tried to think about bodies not so much as sensual presences but to think of their relationship with the typical characters of the comic in terms of proportion. I inverted the proportion of space dedicated to the landscape in relation to the characters, placing minuscule characters in a boundless landscape.

Stefano Ricci When I started drawing I did civil service in an ambulance for two years. One day, for a geometry of destiny, the switchboard called us as we were about to finish a nine-hour shift and told us to go to 13 Montello road, which was where I lived.

I grew up with my grandfather there, my father always worked so I spent all of my time with him. He often said that he wanted to die on his feet. He was 96 years old and two days before the ambulance went to the house where I lived he had bought two white John Player Special bathrobes. We went inside, there were two of us, me and the driver; I went into the bathroom, my grandfather was shaving and had fallen, that is, he was leaning against the mirror. He still had a lot of white hair that he kept all slicked back, he was wearing the white John Player Special bathrobe, long white socks and white slippers. It was indeed a sacred body.

Yesterday, at the Marlene Dumas exhibition, I saw a short film which is an excellent example of how a person, an artist, is a body inhabited by a multitude of conditions which, when transformed into painting, produce a multitude of different points of view.

It is hard to explain, but the film was the Super 8 image Dumas recorded of her daughter, who was in her twenties at the time. Her daughter is lying down, asleep, the sheet partly covers her and partly not, and Marlene Dumas films her. I can be wrong, but it is as if we saw more than one person picking up the camera: a mother (at least I thought I saw a mother) looking at this magnificent, turgid, fertile, innocent flower sleeping, full of beauty.

Then at some point she films her from another point of view and I felt that she was looking at her as I would look at her, that is, with desire.

Then there is another moment where you also feel all the bewilderment of the fact that Dumas is looking in a mirror, she is filming the mirror and her own reflection. I thought: Where will she stop? At that point the camera approaches the body and a hand with the wedding ring emerges from the edge of the sheet, and the gaze stops there. Here are all the looks that Dumas was able to make happen. It takes a lot of courage, in my opinion, to do such a thing.

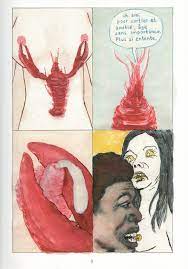

Ilaria Tontardini I am going to ask Dominique one last question, again on the topic of bodies. Before you were talking about brutality and grace, about the need to work on opposite sensations to show what cannot be seen. I was thinking of the book Plus si entente, which you wrote together with Kaï Pfeiffer: the body of a woman who has experienced the unspeakable pain of losing her daughter is put at the center, a body that encompasses beauty and violence. How do you relate to the representation of intimacy, which is also, in part, the life of the body?

Dominique Goblet The matter is very complex and would deserve more time, so I prefer to talk about the creative process behind this book. Plus si entente is a work of pure fiction, even if there is a trace of oneself in every fictional work. I made it with Kaï Pfeiffer, who lives in Berlin, so we had to invent a way of working remotely. We worked on pages divided into four panels in which to write and draw in a very open and free way: one person started and the other reacted, like a sort of ping pong. In the end we mixed everything, trying to understand if a narrative could emerge from that process.

At the center of the story is a woman who invites all the men she has met through dating apps to her home and tries to live like an empress, promising them the ultimate reward: her body.

The characters do not fall into the stereotypes of comics, because I love working on ambiguity. I think it is fundamental, both in comics and in life. I can find a disgusting man handsome and vice versa; beauty as we describe it usually doesn't interest me. I prefer to look for the beauty behind the not beautiful things. I would have liked to call Ostende, my latest book, Derrière, "behind". All that is hidden interests me.

Notes on the contributors

Stefano Ricci

Stefano Ricci is an internationally acclaimed Italian cartoonist and illustrator. His work is always threading on the borders between illustration and comics, painting and experimental writing, visual arts and music. Since 1985 he has collaborated with the alternative press both in Italy and abroad (some of his stories have appeared on magazines such as "Frigidaire", "Dolce Vita", "Linea d'ombra", "il manifesto", "Esquire", "Panorama", "LesInrockuptibles", " Lo Straniero" "la Repubblica "), some of them featuring collaborations with artists such as Philippe de Pierpont (Tufo, Amok 1996) and Gabriella Giandelli (Anita, avant-verlag 2001). Some of his most influential works are La storia dell'orso (Quodlibet 2016); Eccoli (Quodlibet 2015), a graphic memoir combining his childhood memories and a short documentary shot at a former asylum in Gorizia; Bartleby le scribe (Futuropolis 2021) a visual adaptation of Herman Melville's novel; Mia madre si chiama Loredana (Quodlibet 2021) a touching portrait of the artist's mother built on the juxtaposition of visual and narrative fragments. He has worked in theater, dance and cinema productions; he was selected by the ADI, Design Index 2000, and the 2001 Compasso d'Oro award for his design and illustration projects. Together with Giovanna Anceschi, since 1995 he curated the publishing house Edizioni Grafiche Squadro, based in Bologna and specialized in avant-garde comics and illustration, and the following year he founded "MANO", one of the most important magazine in the Italian underground publishing history. He is also among the founders of Sigaretten Edizioni, an independent publishing house based in Bologna that focuses on promoting young artists and rediscovering alternative gems by some of the most important international cartoonists.

He teached comics at the University of Udine, the Hamburg University of Applied Arts and the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna.

Dominique Goblet

Dominique Goblet is a Belgian visual artist, illustrator and pioneer of the European graphic novel. She is one of the most prominent artists of the alternative publishing house Frémok (FRMK), which in the 90s has been a major influence on the independent Franco-Belgian and European comics scene, challenging traditional notion of comics and defying mainstream trends through incessant artistic research and the production of avant-garde comics. Goblet in particular has worked on an experimental approach to comics language, playing extensively with the fragmentation of narrative space and traditional plots, and fostering a fruitful contamination between comics, illustration, painting and contemporary art. Among her most influential works: her debut Portraits Crachés (Fréon 1997), a collection of stories and illustrations previously appeared in the magazine "Frigorevue"; Souvenir d'une journée parfaite (Fréon 2001); her most known graphic novel Faire semblant c'est mentir (L'Association 2007; published in ths US by The New York Review Comics in 2017 with the title Pretending is Lying), an unconventional memoir merging her experiences with alcoholism and child abuse and the story of a lover tormented by an ancient lost love; Les Hommes Loups (FRMK 2010); Chronographie (FRMK 2010), a collection of portraits Goblet and her daughter made of each other during the span of ten years; Plus si entente (Actes Sud BD 2014), made in collaboration with Kai Pfeiffer. Her latest book is Ostende (FRMK 2022), an experiment in landscape painting that pushes further her exploration of fragmented narratives.

Ilaria Tontardini

Ilaria Tontardini is a lecturer of History of Illustration at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna. Since 2005 she is part of Hamelin, where she curates projects dedicated to comics and illustration and is among the organizers of BilBOlbul International Comics Festival.